August 22 2006. A further survey of the two latest strandlines between Chalkwell station and Shelter (0.6 km) showed a return to winter debris in the form of the brown alga

Ascophyllum among the summer green algae. A few large common crabs were present, a large one with legs stranded dorsal-up and more numerous separated dorsal carapaces stranded ventral-up; concave-up in terms of hydrodynamics. There were also some stranded reeds, twigs and human-worked wood debris, which had not come directly from the marshes as the latest tides were all relatively low (predicted as slightly higher, 2.5 m above mean sea-level in latest tide studies around 1 p.m.). A characteristic feature of August strandlines was evident in the form of abundant adult feathers of Black-Headed Gulls, which were also seen alive and well on the beach, and locally molt at this time. My experience is that when floated in closed plastic bottles of seawater they remain largely intact and still do not sink (since August 9 1999, molted on grass inland at Leigh-on-Sea) but in more agitated and open tanks they soon break-up releasing separated calamus, rhachis and vane fragments which can sink despite initially being hollow and full of air. On December 4 2005 I refloated both dried and recently stranded primary wing feathers of the Great Black-Backed Gull

Larus marinus L, mainly cut into the calamus (quill) and the remaining rhachis plus vane, in the diurnally agitated seawater tanks. The six calamus sample had cut dimensions of 145 mm boy 6 mm diameter, and their separated vanes had lengths ranging from 213 to 247 mm. Recently a few of the calamus samples have sunk apparently unchanged, while the others have lost all or most of their vanes and distal rhachis before sinking. By August 30, day 269 of floatation in the more open conditions there were just two calamus samples still floating horizontally, with one uncut feather which is not reduced to a total length of 350 mm lacking any trace of a vane and the tip of the rhachis. By contrast the black cormorant tail feather, stranded and refloated in the same experimental conditions on January 3 2006, sank in a macroscopically intact condition on August 4 (day 212). The black melanin probably resists decay and brittleness of the white keratin, but there is probably a better adaptation of the deep-diving feathers of cormorants against waterlogging. In addition they have a greater initial density, making them sink quicker when refloated than the relatively hollow structure of gull and other more typical bird feathers. This denser structure and the melanin doubtless contributes to their lower rate of decay, which in gull feathers is due to brittle fracturing of the keratin, rather than obvious bacterial growth. However it is also possible that cormorant feathers also contain more wax or oils than gull feathers. One can of course see the cormorants standing with their wings open to dry them while the gulls and other marine birds do not bother and are much better fliers despite this careless indifference to feather drying. Terrestrial birds even go to the trouble of getting their feathers wet in freshwater, rather than worry about his effect on wing density after a bath.

The more unusual and attractive feathers seen stranded on August 22 have continued to float in the same tank until August 30 without showing signs of damage. A sample of 8, with lengths of 116 to 131 mm and vane widths of 18 to 38 mm (when dry), showed the common characteristics of 8 to 12 transverse brown bands or triangular bars on the generally white background of the vane. The calamus and rhachis were mainly white, but with a grey more translucent proximal end to the calamus, and a shore central band of brown within the white proximal end of the rhachis. It was not clear to me what these feathers were, but since they were spread out on two adjacent strandlines over a 0.6 km distance they did not result from a single drowned woodpecker or similar non-marine species. The tail and secondary wing feathers of a local wading bird the Curlew

Numenius arquata (L.) seem to be the most likely candidate judging from

Tracks and Signs of the Birds of Britain and Europe by Brown

et al. (2003, Christoper Helm, Publisher London 333 pp.). The main problem with that identification is that the similar-looking, larger primary wing feathers, were not seen among the gull feathers of that size; perhaps because they are not molted at the same time as the secondary and tail feathers.

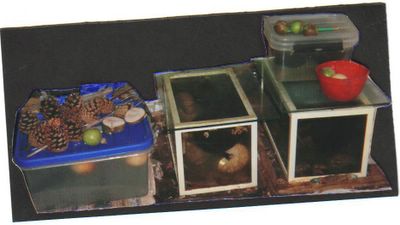

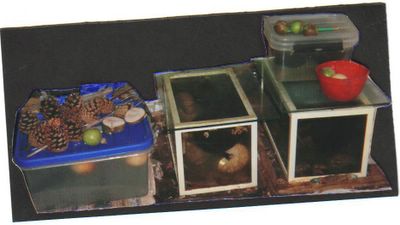

Incidentally the two large pinecones floated and described on April 7 2006, also sank on the tank containing the gull calamus samples on August 2-4 after slight cooling of the warm seawater.